Beylik of Tunis

Beylik of Tunis بايليك تونس (Arabic) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1705–1881 | |||||||||

| Motto: يا ذا الألطاف الخفية احفظ هذه المملكة التونسية "Oh God of hidden kindness, save this Kingdom of Tunis" | |||||||||

| Anthem: Salam al-Bey (Beylical Anthem) | |||||||||

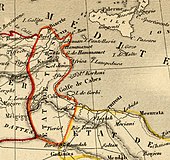

Kingdom (Beylik) of Tunis in 1707 | |||||||||

| Capital | Tunis | ||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

| Government | Constitutional Monarchy | ||||||||

| Bey | |||||||||

• 1705–1735 | Hussein I | ||||||||

• 1859–1881 | Muhammad III | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1759–1782 | Rejeb Khaznadar | ||||||||

• 1878–1881 | Mustapha Ben Ismaïl | ||||||||

| Legislature | Supreme Council | ||||||||

| Historical era | Late modern period | ||||||||

| 15 July 1705 | |||||||||

| 12 May 1881 | |||||||||

| Currency | Rial | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Tunisia | ||||||||

| History of Tunisia |

|---|

|

|

|

The Beylik of Tunis (Arabic: بايليك تونس), also known as Kingdom of Tunis[1] (Arabic: المملكة التونسية) was a largely autonomous beylik of the Ottoman Empire located in present-day Tunisia. It was ruled by the Husainid dynasty from 1705 until the establishment of the French protectorate of Tunisia in 1881. The term beylik refers to the monarch, who was called the Bey of Tunis. Under the protectorate, the institution of the Beylik was retained nominally, with the Husainids remaining as largely symbolic sovereigns.[2][3][4]

The Beys remained faithful to the Sublime Porte, but reigned as monarchs after gradually gaining independence from the Ottoman Empire. Between 1861 and 1864, the Beylik of Tunis became a constitutional monarchy after adopting the first constitution in Africa and in the Arab world. The country had also its own currency and an independent army, and in 1831 it adopted its flag, which is still in use today.[5]

The institution of the Beylik was finally abolished one year after indepedence on the 25th july, 1957, and a republic was declared.

History[edit]

Establishment of the beylik (1705–1735)[edit]

Following the Revolutions of Tunis which saw Ibrahim Sharif overthrow Muradids' power, the latter became the first bey to combine this function with that of Pasha. Taken to Algiers following a defeat against the Dey of Algiers, and unable to put an end to the troubles which agitated the country, he was a victim, on 10 July 1705 of a coup of Al-Husayn I ibn Ali, who took the name of Hussein I.

Hussein I reigned alone over Tunisia, establishing a real monarchy and became Possessor of the Kingdom of Tunis, disposing over all his subjects the right of high and low justice. His decrees and decisions had the force of law.[6]

As Bey of Tunis he sought to be perceived as a popular Muslim interested in local issues and prosperity. He appointed as qadi a Tunisian Maliki jurist, instead of an Hanafi preferred by the Ottomans. He also restricted the legal prerogatives of the janissary and the Dey. Under Hussein I, support was provided to agriculture, especially planting olive orchards. Public works were undertaken, e.g., mosques and madrassa (schools). His popularity was demonstrated in 1715 when the kapudan-pasha of the Ottoman fleet sailed to Tunis with a new governor to replace him; instead Hussein I summoned council, composed of local civil and military leaders, who backed him against the Ottoman Empire, which then acquiesced.[7]

Wars and crisis to take the throne (1735–1807)[edit]

In 1735, Ali I gained access to the throne by dethroning his uncle Hussein I who was killed by his great-nephew Younès in 1740.[8]

In 1756, Ali I was in turn overthrown by the two sons of his predecessor who seized Tunis with the help of the governor of Constantine: Muhammad I Rashid (1756–1759) and Ali II (1759–1782).[9]

Algerian attempts to overthrow the Beys did not end until 1807, with a victory for the Tunisians led by Hammouda I.[8]

Stability and reforms (1807–1869)[edit]

In the 19th century, the country underwent profound reforms, thanks to the reformist action of Kheireddine Pacha and his close advisers: the Minister of the Interior General Rustum, the Minister of Instruction General Hussein, the Minister Bin Diyaf and the ulama Mahmoud Kabadou, Salem Bouhageb and Mokhtar Chouikha.

Among these, are the abolition of slavery, the foundation of the military school of Bardo in 1840, the Sadiki College in 1875, and the adoption in 1861 of the first constitution of Africa and the Arab world, becoming a constitutional monarchy.[10]

Financial crisis and foreign interference (1869–1881)[edit]

The financial crises in the country followed, with Mustapha Khaznadar as prime minister, which constituted an opportunity for European intervention in Tunisia. Thus, the Financial Commission, an international financial committee, was formed in 1869,[11] under pressure from some European countries, in a circumstance in which the Tunisian financial crisis intensified and it became impossible for the state to pay its foreign debts, which at that time amounted to 125 million francs.

This committee was placed under the chairmanship of the reformed minister Kheireddine Pacha, and later devolved to Mustapha Ben Ismail, and it also included representatives of the creditor countries (Italy, England, and France). The Commission was one of the manifestations of foreign interference in the internal affairs of Tunisia by subjecting its finances to international control. The country's revenues were divided into two parts, one part allocated to the state's expenditures and the other to the payment of its debts. So the Bey was restricted, he could no longer grant any concession or conclude any loan agreement except with the approval of the Commission, which acted as a Tunisian Ministry of Finance. This facilitated the conclusion of a bilateral treaty between Tunisia and France in 1881 stipulating France's protection of Tunisia, and consequently, the French protectorate was established.

Government[edit]

| Bey of Tunis | |

|---|---|

| |

Muhammad III The Bey who was before the French protectorate in 1881 | |

| Details | |

| First monarch | Hussein I |

| Last monarch | Muhammad VIII |

| Formation | 15 July 1705 |

| Abolition | 20 March 1956 |

| Residence | Beylical Palace of Bardo |

| Appointer | Hereditary |

| Pretender(s) | Prince Ali |

The Beylik of Tunis was a constitutional (1861–1864) and hereditary monarchy with legislative power being exercised by the monarch in conjunction with Supreme Council.

Bey[edit]

The Bey is considered the leader of the Husainid dynasty, the head of the state, the symbol of its unity, and the protector of its borders. He also exercises power through the government and the Supreme Council, as stipulated in Article 12 of the 1861 Constitution.[12]

What distinguishes the system of government at that time, is that the monarch is responsible before Supreme Council in accordance with Article 11 of the Constitution, which is one of the first countries in the world to stipulate it.[12]

Article 13 of the constitution affirmed that the Bey (monarch) is the supreme commander of the Tunisian armed forces, and Article 9 affirmed as well that the 1857 Fundamental Pact must be respected by him.[12]

Although the constitution limited his powers, he had the ability to appoint members of the Supreme Council, in addition to the fact that laws are issued in his name.

The Bey must be the eldest of the Husainid dynasty. The second after him becomes Bey El Mahalla (Bey of the Camp), which was a title for the heir apparent to throne. The title came the style of Highness. The last person to carry this title was Prince Husain Bey, Bey al-Mahalla.

Prime Minister[edit]

The Prime Minister of Tunisia during the era of the Beylik is the head of the government who was responsible for its affairs and was appointed and dismissed by the Bey. This office was created in 1759 with the beginning of the rule of Ali II and Rejeb Khaznadar was the first to take it, becoming the first Prime Minister in the history of Tunisia.

With its creation, this office was the preserve of the Mamluks of foreign origin who were brought to Tunisia at a young age in order to serve the Royal Family and the Makhzen, such as Mustapha Khaznadar, Kheireddine Pacha and others.

Mohammed Aziz Bouattour is considered the first indigenous Tunisian to hold the office in 1882, and by the way, he is the longest-serving Prime Minister in the history of Tunisia with a period of nearly 25 years, and during his term, the French protectorate was established in Tunisia.

The Prime Minister of Tunisia had an important authority in the 19th century, as everything related to the Royal Family was kept in his office according to Article 2 of the Constitution.[12]

The Prime Minister, based on Section 9 of the Constitution, prepares the budget presented to him by the Ministry of Finance and submits it to Parliament in accordance with Article 64.[12]

Legislature[edit]

The Tunisian parliament was called the Supreme Council (Arabic: المجلس الأكبر). It was an institution that was established during the reign of Muhammad III in a period characterized by the adoption of many reforms, including the declaration of the Fundamental Pact (1857), the Tunisian Journal[13] (1860) and the adoption of the Constitution (1861).

According to Article 44 of this constitution, this council was composed of 60 members: 20 members were chosen among the senior officials and high-ranking officers of the state, and 40 chosen among the notables who do not receive remuneration. Among its members were Ahmad ibn Abi Diyaf and Giuseppe Raffo.[12]

The functions of the Council were fixed in Chapter 7 of the Constitution. The most important of these functions were to legislate, revise, explain and interpret laws, approve taxes, monitor ministers, and discuss the budget. These functions confirmed the importance of the Supreme Council as an institution that was at the same time legislative, financial, judicial and administrative.[12]

This council was abandoned in 1864 after the Mejba Revolt.

Politics[edit]

Authority of the Bey[edit]

Husainid policy required a careful balance among several divergent parties: the distant Ottomans, the Turkish-speaking elite in Tunisia, and local Tunisians (both urban and rural, notables and clerics, landowners and remote tribal leaders). Entanglement with the Ottoman Empire was avoided; yet religious ties to the Caliph were fostered, which increased the prestige of the Beys and helped in winning approval of the local ulama and deference from the notables. Janissaries were still recruited, but increasing reliance was placed on tribal local forces. Turkish was spoken at the apex, but use of Tunisian Arabic increased in government use. Kouloughlis (children of mixed Turkish and Tunisian parentage) and native Tunisians notables were given increased admittance into higher positions and deliberations. The Husainid Beys, however, did not themselves intermarry with indigenous peoples; instead they often turned to the institution of mamluks for marriage partners. Mamluks also served in elite positions.[14] The local ulama were courted, with funding for religious education and the clerics. Local jurists (Maliki) entered government service. Marabouts of the rural faithful were mollified. Tribal sheikhs were recognized and invited to conferences. Especially favored at the top were a handful of prominent families, Turkish-speaking, who were given business and land opportunities, as well as important posts in the government, depending on their loyalty to the Bey of Tunis.[15][16]

Relations with Europe[edit]

The French Revolution and reactions to it negatively affected European economic activity leading to shortages which provided business opportunities for Tunisia, i.e., regarding goods in high demand but short in supply, the result might be handsome profits. The capable and well-regarded Hammouda Pasha (1782–1813) was Bey of Tunis (the fifth) during this period of prosperity; he also turned back an Algerian invasion in 1807, and quelled a janissary revolt in 1811.[17]

After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Britain and France secured the Bey's agreement to cease sponsoring or permitting corsair raids, which had resumed during the Napoleonic conflict. After a brief resumption of raids, it stopped.[18] In the 1820s economic activity in Tunisia took a steep downturn. The Tunisian government was particularly affected due to its monopoly positions regarding many exports. Credit was obtained to weather the deficits, but eventually the debt would grow to unmanageable levels. Tunisia had sought to bring up to date its commerce and trade. Yet different foreign business interests began to increasingly exercised control over domestic markets; imports of European manufactures often changed consumer pricing which could impact harshly on the livelihood of Tunisian artisans, whose goods did not fare well in the new environment. Foreign trade proved to be a Trojan Horse.[19][20]

[edit]

Activities of maritime corsairs were important at that time because independence from the sultan led to the decline of its financial support and Tunisia therefore had to increase the number of its catches at sea in order to survive.

The Tunisian Navy reached its peak during the reign of Hammouda I (1782–1814), where ships, leaving from the ports of Bizerte, La Goulette, Porto Farina, Sousse, Sfax and Djerba, seized Spanish, Corsican, Neapolitan, Venetians, etc. The Tunisian government maintained during this period from 15 to 20 corsairs, the same number of them being attached to companies or individuals, among whom sometimes high-ranking figures such as the Keeper of the Seals Moustapha Khodja or the caïds of Bizerte, Sfax or Porto Farina, and give the government some of their catches, which include Christian slaves.[21]

The peace treaties, which multiplied in the 18th century (with Austria in 1748 and 1784, Venice in 1764–1766 and 1792, Spain in 1791 and the United States in 1797) regulated the navy and limited its effects.[22]

First of all, the treaties imposed requirements (possession of authorizations for ships and passports for people) and also identified the conditions for catches at sea (distance from the coast), so as to avoid possible abuses. The situation remained the same until the Congress of Vienna and the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle when European countries summoned Tunisia to put an end to this, which would be effective and definitive after the intervention of France in this question in 1836.

Financial policy[edit]

The taxes in Tunisia in 1815 (2,2 million gold francs) were not profitable. At the same time, the Bey coveted Tripolitania. In 1848, to maintain his army of 5,000 soldiers, the Bey increased taxation, which provoked a revolt, finally put down. Taxation is reduced, but a loan of 35 million gold francs, at a rate of 7%, is contracted with French bankers.

However, reckless spending continued: a Versailles-style palace, in Mohamedia, and another in La Goulette, a military school and an arsenal. Worse, the finance minister Mahmoud Ben Ayed fled to France with the government budget.[23] However, the diversions continued under his successors. This situation pushed the speaker of the Supreme Council, Kheireddine Pacha, to resign and the Supreme Council to be dissolved.

At the beginning of 1864, a serious crisis broke out due to poor financial management on the part of Prime Minister Mustapha Khaznadar: the public debt, heavy loans abroad contracted under catastrophic conditions (continuation of embezzlement) and doubling of the tax lead to a new revolt of the tribes of the center of the country who refused to pay this tax. Shortly after the Revolt of Mejba, the Bey ordered to collect the taxes. At the same time, Haydar Afendi, ambassador of the Ottoman Empire, arrived with financial aid to remedy the situation. The sum offered is entrusted by the Bey to Khaznadar. But the latter recovered this sum for his personal use. Once again, a loan of 30 million gold francs had to be contracted, which provoked the intervention of the European countries (in particular France). In this context, the constitution was even suspended on 1 May 1864.[24]

Major reforms[edit]

Sovereign state[edit]

Tunisia was one of the first countries in the region to adopt the pillars of modern state sovereignty. The Beylik adopted a national flag distinguished from the rest. In fact, several Muslim countries along the south coast of the Mediterranean Sea used a plain red naval flag.[25] After the destruction of the Tunisian naval division at the Battle of Navarino on 20 October 1827,[26] the Bey Hussein II decided to create a flag to use for the fleet of Tunisia, to distinguish it from other fleets. It has been adopted as the national flag of Tunisia since 1831 until now.[27] This made the Tunisian flag the oldest Arab and African flag, and among the ten oldest flags in the world.

The coat of arms has been adopted also since the beginning of the 19th century in red and green, which are the colors of the ruling Husainid dynasty. The coat of arms's colors had an impact on Tunisian public culture. Because these colors are also those of the football club of the Stade Tunisien which was under patronage of the royal family. They are also found in Tunisian pastries: one, called Bey sigh, is made of pink, green and white marzipan; the other, called bey's baklawa, is a form of Tunisian baklava.

A new coat of arms for Tunisia was adopted in 1858 during the reign of Sadok Bey, while preserving the same green and red dynasty colors, according to Henry Dunant after his visit to Tunisia, with the modernization of the national emblem and the addition of the phrase Oh God of hidden kindness, save this Kingdom of Tunis. This was due to that period in which epidemics abounded in the Kingdom and led to human losses, in addition to the spread of Sufism in Tunisian culture, which used to call God as the owner of hidden kindness, influenced by Sidi Belhassen Chedly.

Tunisia also adopted a national anthem as one of the pillars of national sovereignty, and that was in 1846, it was called Salam El Bey (Beylical anthem). It was sung in honour of the Bey. Initially without lyrics, but words were written by an unknown poet and were adapted to the melody of the anthem. According to historian Othman Kaak, the music was composed by Giuseppe Verdi.

European trade[edit]

Starting early in the 19th century, Tunisia came increasingly under European influence. Under the Husainid Beys, trade and commerce with the Europeans increased year after year. Permanent residences were established in Tunis by many more foreign merchants, especially Italians. In 1819, the Bey agreed to quit with finality corsair raids. Also the Bey agreed with France to terminate his revenue policy whereby government agents dominated foreign trade by monopolizing the export of Tunisian goods; this change in policy opened the country to international commercial firms. In 1830 the Bey accepted to enforce in Tunisia treaties, in which European merchants enjoyed extraterritorial privileges, including the right to have their resident consuls act as the judge in legal cases involving their national's civil obligations.[28] Also in 1830 the French royal army occupied the central coastal lands in neighboring Algeria.[29] At that time, they were inexperienced about and lacked the knowledge of how to develop a colony.[30]

Military policy[edit]

After defeating Algeria in 1807, the army maintained the same structure, but Ahmad I wanted to change the military policy and was keen to reform and modernize the armed forces, especially since France occupied Algeria in 1830 and its army became a threat to Tunisia. He was also influenced by what he saw during his visit to France of architectural progress, especially in the organization of their army, which made him want to follow their strategy and form a Tunisian army on the French style.

In a major step, the Bey initiated the recruitment and conscription of individual Tunisians (instead of foreigners or by tribes) to serve in the army and navy, a step which would work to reduce the customary division between the state and its citizens.[31] So, he founded the Bardo Military School in 1840 for Tunisian soldiers to graduate from, relying on French assistance. He also worked to provide the necessary equipment to improve the army, so he took care of some industries, such as the gunpowder industry in Tunisia, and created a sophisticated navy.

As part of his maneuvering to maintain Tunisia's sovereignty, Ahmed Bey sent 4,000 Tunisian troops against the Russian Empire during the Crimean War (1854–1856). In doing so he allied Tunisia with Turkey, France, and Britain.[32]

Abolition of Slavery[edit]

On 29 April 1841, Ahmed I Bey had an interview with Thomas Reade who advised him to ban the slave trade. Ahmed Bey was convinced of the necessity of this action; and he was considered open to progress and quick to act against all forms of fanaticism. He decided to ban the export of slaves the same day that he met with Reade. Proceeding in stages, he closed the slave market of Tunis in August and declared in December 1842 that everyone born in the country would thereafter be free.[33]

To alleviate discontent, Ahmed obtained fatwas from the ulama beforehand from the Bach-mufti Sidi Brahim Riahi, which forbade slavery, categorically and without any precedent in the Arab Muslim world. The complete abolition of slavery throughout the country was declared in a decree of 23 January 1846.[34][35] However, although the abolition was accepted by the urban population, it was rejected (according to Ibn Abi Dhiaf) at Djerba, among the Bedouins, and among the peasants who required a cheap and obedient workforce.[36]

This resistance justified the second abolition announced in a decree of Ali III Bey on 28 May 1890.[37] This decree promulgated financial sanctions (in the form of fines) and penal sanctions (in the form of imprisonment) for those who continued to engage in the slave trade or to keep slaves as servants. The colonial accounts tended to pass over the first abolition and focus on the second.

Fundamental Pact 1857[edit]

The Fundamental Pact of 1857 (Arabic: عهد الأمان) is a declaration of the rights of Tunisians and inhabitants in Tunisia promulgated by Muhammad II on 10 September 1857, as part of the reforms of the Kingdom of Tunis.[8]

This pact provided revolutionary reforms: it proclaimed that everyone is equal before the law and before taxes, established freedom of religion and trade, and gave foreigners the right of access to property and exercise of all professions. This pact abolished the status of dhimmi for non-Muslims.[38]

The pact was translated into Hebrew in 1862 and was then the first non-religious document to be translated into this language in Tunisia.

Considering this pact as a political genius act, Napoleon III awarded the grand cordon of the Legion of Honor with diamond insignia to Mohammed Bey at the Bardo Palace on 3 January 1858.[39]

On 17 September 1860 in Algiers, Napoleon III awarded Sadok Bey, brother and successor of Mohammed Bey, the Grand Cordon of the Legion of Honor after he received from the latter a magnificent volume of the Fundamental Pact.[39]

Tunisian Journal 1860[edit]

The publication of the Tunisian Journal (Arabic: الرائد التونسي) was accompanied by a policy of modernization reforms.[40] The first version was issued on 22 July 1860,[41] and thus was the first official Arabic newspaper published weekly in Tunisia, and specialized in publishing royal orders and government decrees, in addition to an unofficial section of political news and literary issues. (The first private Arabic newspaper in Tunisia, Al-Hadira, would not be published until 1888.)[42]

A number of Zitouna University professors who were loyal to reform and to Minister Kheireddine Pacha, such as Mahmoud Kabado, Salem Bouhageb, Bayram V, and Mohamed Snoussi were elected to the editorial in the government Journal.

The publication of the Journal continued from 1860 to 1882, during which the editors supported the reform-modern trend led by Minister Kheireddine Pacha.

The issuance of the Journal at that time was considered an important sign of modernizing the state and making individuals aware of the laws issued by the Bey and the government, although it was an opportunity for the political authority to give justification for its actions and legitimize its reforms. After the establishment of the French protectorate, it became a purely legal official journal in 1883, thus ending its literary and cultural role, and its name became the Official Tunisian Journal. With the proclamation of the Republic in 1957, its name was changed to the Official Journal of the Tunisian Republic, and it is issued to this day under this name.

Constitution of 1861[edit]

Following the Fundamental Pact, a commission was set up to draft a real constitution; it was submitted on 17 September 1860 to Muhammad III, the new Bey after Muhammad II. The constitution came into effect on 26 April 1861. It was the first written constitution in Arab lands,[43] as well as the first constitution established by a Muslim-majority country.[44]

The text of 114 articles established a constitutional monarchy with a sharing of power between an executive branch consisting of the Bey and a prime minister, with important legislative prerogatives to a Supreme Council, creating a type of oligarchy. It established an independent judiciary; however the guardian of the constitution was the legislature which had sovereign authority to review unconstitutional acts by the executive. In addition, the sovereign was not free to dispose of the resources of the state and must maintain a budget, while he and the princes of his family were to receive stipends. Issues of national representation and elections were omitted. In fact in actual practice the members of the Supreme Council were appointed more through cronyism and favor swapping than national interest. Many of the old Mamluk class were appointed, keeping the bureaucracy firmly in Mamluk hands. For this reason, and others such as the provision for general military conscription and retaining the provisions granting rights to foreign nationals, many did not approve of the Bey's actions. Universal application of the mejba (head tax), under the equal taxation clause, incurred the wrath of those who had formerly been exempt: the military, scholars/teachers and government officials. Matters came to a head in 1864 when traditionalist Ali Ben Ghedhahem led a revolt against the Bey. The constitution was suspended as an emergency measure and the revolt was eventually suppressed. Ali Ben Ghedhahem was killed in 1867.[45][46]

Bankruptcy and establishment of protectorate[edit]

Due to the ruinous policies of the Bey and his government, rising taxes and foreign interference in the economy, the country gradually experienced serious financial difficulties. All this forced the government to declare bankruptcy in 1869 and to create an international Anglo-Franco-Italian financial commission chaired by the inspector of finances Victor Villet.

In 1873, Villet unveiled the diversions of Khaznadar who was replaced by Kheireddine Pasha. But Kheireddine's reforms displeased the oligarchs who forced him to resign in 1877. This was an opportunity for European countries (France, Italy and the United Kingdom) to enter the country.

Because Tunisia quickly appeared as a strategic issue of great importance due to the geographical location of the country, between the western and eastern basin of the Mediterranean. Tunisia is therefore the object of the rival desires of France and Italy: France had wishes to secure the borders of French Algeria and prevent Italy from thwarting its ambitions in Egypt and the Levant by controlling access to the Eastern Mediterranean.

Italy, faced with overpopulation, wanted a colonial policy in Tunisia, where the European minority were Italians.[47] The French and Italian consuls tried to take advantage of the Bey's financial difficulties, with France counting on the neutrality of England (unwilling to see Italy take control of the Suez Canal route) and benefiting from Bismarck, who wanted divert it from the question of Alsace-Lorraine.[47] After the Congress of Berlin from 13 June to 13 July 1878, Germany and England allowed France to put Tunisia under protectorate and this to the detriment of Italy, which saw this country as its reserved domain.

The incursions of Khroumir "looters" into Algerian territory provided a pretext for Jules Ferry, supported by Léon Gambetta in the face of a hostile parliament, to stress the need to seize Tunisia.[47]

In April 1881, French troops entered without major resistance and managed to occupy Tunis in three weeks, without a fight.[48] On 12 May 1881, the protectorate was formalized when Sadok Bey, threatened with being dismissed and replaced by his brother Taïeb Bey, signed the Bardo Treaty at the Palace of Ksar Saïd. Prime Minister Mustapha Ben Ismail encouraged him also to sign the treaty. This allowed, a few months later, the French troops to face uprisings in Kairouan and Sfax.[47]

Architecture[edit]

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Husainid Beys sought to improve Tunisia's infrastructure and to develop existing palaces and schools. Under Hussein I, founder of the Husainid dynasty, the Zawiya of Sidi Kacem El Jellizi was restored and expanded. A decorated courtyard, a prayer hall, and the pyramidal green roof of the mausoleum were added at this time.[49]: 227–228 He also transformed the Bardo Palace into a massive fortified complex with various amenities including a mosque, a madrasa, a hammam and a market. It continued to be expanded by later rulers.[49]: 229–230 His successor, Ali I, built four madrasas, more than any other previous ruler in Tunisia. The madrasas he built are distinguished by their rich decoration of marble paneling, carved stucco, and Qallalin tiles. Two of them, the Madrasa El Bachia (1752) and the Madrasa Slimania (1754), are located behind the Zitouna Mosque, near his mausoleum.[49]: 229 [50]

Various other palaces were also built in Tunis and the surrounding areas. Hammouda I built another palace, Dar El Bey, near the Kasbah of the city, and another one called Mannouba Palace. A summerhouse from the latter was relocated in the 19th century to the present-day Belvedere Park in Tunis.[49]: 231 Other examples of private mansions built in the old city of Tunis during this period include Dar Hussein, built in the 18th century and expanded and decorated again in the early 19th century, Dar Ben Abdallah, dated to 1796, and Dar Lasram, built in the early 19th century.[51][52]: 477–478

There was a desire to incorporate European-style elements as well. For example, most of the Husainid Beys, along with many of their family members and close associates, were buried in a mausoleum known as Tourbet el Bey, which includes decorative details in an Italianate style. One of the last and most impressive mosques of this era is the Saheb Ettabaâ Mosque (one of Hammouda's ministers) in Tunis, built between 1808 and 1814. It is similar again to the Youssef Dey Mosque, with decoration mixing both local and European influences.[49]: 233–234

Great attention was paid to the educational infrastructure as well, so the Sadiqiyah School was built in 1875 by the Prime Minister Khair al-Din Pasha and was named in honor of Sadiq Bey. The school developed advanced educational programs and included teaching methods in French and Italian. Ahmed Bey also inaugurated the first military school in the entire region, which is the Bardo Military School in 1840, which is concerned with graduating military personnel.[citation needed]

Ahmed Bey also tried to build a French-style palace after his visit to France and his great admiration for the Versailles Palace, so he ordered the construction of the Muhammadiyah Palace in 1846, and the works took on an important dimension, so the import of marble from Carrara, porcelain from Naples, chandeliers and mirrors from Venice.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Thomas Shaw (16 June 2022). "Map of the Kingdom of Tunis dating from 1743". Catalogue général.

- ^ Cooley, Baal, Christ, and Mohammed. Religion and Revolution in North Africa (New York 1965), pp. 193–196.

- ^ Richard M. Brace, Morocco Algeria Tunisia (Prentice-Hall 1964), pp. 36–37.

- ^ Jamil M. Abun-Nasr, A History of the Maghrib (Cambridge University 1971), pp. 278–282.

- ^ Jean Ganiage (1994). "Contemporary history of the Maghreb from 1830 to the present day" (in French). Paris: Fayard.

- ^ Ali Mahjoubi (1977). "The establishment of the French protectorate in Tunisia" (in French). Tunis: Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences of Tunis..

- ^ Abun-Nasr, A History of the Maghrib (Cambridge University 1971) p. 180.

- ^ a b c Ahmad ibn Abi Diyaf (1990). "Present of the men of our time: chronicles of the kings of Tunis and the fundamental pact" (in Arabic). Tunis: Tunis Edition.

- ^ Perkins, Tunisia (Westview 1986) at 61–62.

- ^ Yves Lacoste / Camille Lacoste-Dujardin (1991). "The state of Maghreb" (in French). Paris: La Découverte.

- ^ "How Tunisia lost its sovereignty in 1869". Jeune Afrique. 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Tunisian constitution of 26 April 1861". Digithèque de matériaux juridiques et politiques. 16 June 2022.

- ^ Jacques Michon; Jean-Yves Mollier (2001). Les mutations du livre et de l'édition dans le monde du XVIIIe siècle à l'an 2000. Actes du colloque international, Sherbrooke, 2000 (in French). Montréal: Presses de l'université Lava. p. 353. ISBN 9782747508131.

- ^ In Tunisian practice, non-Muslim slave youths were purchased in markets, educated with royal scions in high government service and in the Muslim religion, converted, given high echelon posts, and often married to royal daughters. Mamluks would number about 100. Perkins, Tunisia (Westview 1986) at 63.

- ^ Cf., Abun-Nasr, A History of the Maghrib (1971) at 182–185.

- ^ Perkins, Tunisia (Westview 1986) at 62–63, 66.

- ^ Perkins, Tunisia (Westview 1986) at 64.

- ^ Cf., Julien, History of North Africa (Paris 1931, 1961; London 1970) at 328.

- ^ Lucette Valensi, Le Maghreb avant la prise d'Alger (Paris 1969), translated as On the Eve of Colonialism: North Africa before the French conquest (New York: Africana 1977); cited by Perkins (1986) at 67.

- ^ Perkins, Tunisia (Westview 1986) at 64–67.

- ^ Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800. Robert Davis (2004). p.45. ISBN 1-4039-4551-9.

- ^ "Treaty of Peace and Friendship Signed at Tunis (August 28, 1797)". US Embassy in Tunisia. 16 June 2022.

- ^ Lazhar Gharbi, Mohamed (2015). "Mahmoud Ben Ayyed Le parcours transméditerranéen d'un homme d'affaires tunisien du milieu du xixe siècle". Méditerranée. 124: 21–27. doi:10.4000/mediterranee.7641. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Noura Borsali (2008). "Tricentenaire de la dynastie husseinite (15 juillet 1705 – 25 juillet 1957) : les beys de Tunis à l'épreuve du temps et de l'Histoire" (in French). Tunis: Réalités.

- ^ Smith, Whitney (2001). Flag Lore Of All Nations. Brookfield, Connecticut: Millbrook Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-7613-1753-8. OCLC 45330090.

- ^ Bdira, Mezri (1978). Relations internationales et sous-développement: la Tunisie 1857–1864 (in French). Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International. p. 31. ISBN 91-554-0771-4. OCLC 4831648.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20080613175430/http://www.ministeres.tn/html/indexdrapeau.html Retrieved July 2008.

- ^ Stanford J. Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (Cambridge University 1976) at I: 29–30, 97–98, and (re French capitulations of 1569) 177.

- ^ Richard M. Brace, Morocco Algeria Tunisia (Prentice-Hall 1964) at 34–36.

- ^ Balch, Thomas Willing (1909). "French Colonization in North Africa". The American Political Science Review. 3 (4): 539–551. doi:10.2307/1944685. JSTOR 1944685. S2CID 144883559.

- ^ Perkins, Tunisia (Westview 1989) at 69–72.

- ^ Rinehart, "Historical Setting" 1–70, at 27, in Tunisia. A country study (3rd ed., 1987).

- ^ (in French) César Cantu, Histoire universelle, traduit par Eugène Aroux et Piersilvestro Léopardi, tome XIII, éd. Firmin Didot, Paris, 1847, p. 139

- ^ (in Arabic) Original decree of 23 January 1846 on the enfranchisement of slaves (National archives of Tunisia)

- ^ (in French) French translation of the decree of 23 January 1846 on the enfranchisement of slaves (Portal of Justice and Human rights in Tunisia)

- ^ Ibn Abi Dhiaf, Al Ithaf, tome 4, pp. 89–90

- ^ (in French) Décret du 28 mai 1890, Journal officiel tunisien, 29 May 1890

- ^ "Tunisian Dundamental Pact". Digithèque de matériaux juridiques et politiques. 17 June 2022.

- ^ a b Mohamed El Aziz Ben Achour (2003). Beylical Court of Tunis. Espace Diwan. p. 136.

- ^ Jacques Michon; Jean-Yves Mollier (2001). Les mutations du livre et de l'édition dans le monde du XVIIIe siècle à l'an 2000. Actes du colloque international, Sherbrooke, 2000 (in French). Montréal: Presses de l'université Lava. p. 353. ISBN 9782747508131.

- ^ (in French) Tunisie (Arab Press Network) Archived 2011-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Masri, Safwan. Tunisia: An Arab Anomaly. New York: Columbia University Press, 2017, 150–151.

- ^ "coğrafyasında kendi türünün ilki sayılan Kânûnu'd-Devle adlı bir anayasayı ilanla sonuçlandı." ("the first of its kind in Muslim territories.") Ceylan, Ayhan (2008). "Osmanlı Coğrafyasında İktidarın Sınırlandırılması (Anayasacılık): Tunus Tecrübesi (The Restriction of Authority in the Ottoman Geography and Constitutionalism: the Tunisian Experience)". Dîvân: Ilmı̂ araştırmalar (Divan: Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Bilim ve Sanat Vakfı (Science and Arts Foundation). 13 (1 (24)): 129–156, 129.

- ^ Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg. p. 21-51. (info page on book at Martin Luther University) – Cited: p. 38 (PDF p. 40)

- ^ "Ali Ben Ghedhahem" (in French). Fédération des Tunisiens pour une Citoyenneté des deux Rives. 20 September 2009. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ Vovelle, Michael (1990). L' image de la Révolution française. Pergamon Press. p. 1028.

- ^ a b c d Philippe Conrad (2003). "Le Maghreb sous domination française (1830–1962)" (in French). clio.fr.

- ^ Ling, Dwight L. (1979). Morocco and Tunisia, a Comparative History. University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-0873-1.

- ^ a b c d e Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700–1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ "Qantara – Madrasa of Slimaniyya". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2002). Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers, MWNF. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

External links[edit]

.svg/125px-Flag_of_the_Beylik_of_Tunis_(1831–1881).svg.png)